How the End of Work Exposes the Crisis of a Broken System

The Collapse of the Money-centric System

Value is the foundation of human life. It shapes how we live, how we relate to one another, and what we believe matters. Wherever we place value – and whatever we collectively agree has value – becomes the organising principle of our behaviour, our systems, and ultimately our civilisation. The value set we adopt determines not only how we live today, but the consequences that unfold tomorrow.

For most of human history, and certainly in the world we share today, the dominant value set is built around money. Not human experience. Not community. Not contribution. Not wellbeing. Money.

Our governments, institutions, systems of governance, economies, and the very fabric of daily life all orbit this single construct. Everything has become transactional because the value of money – what it costs, what we earn, what we accumulate, what we attract, what we are given – has become the lens through which we make decisions about the present and the future. Our interpretation of how money works, or how it has worked in the past, has become the compass by which we navigate life.

But the problem with money is not new. It began the moment money stopped being a simple medium of exchange – a tool to facilitate trade – and instead became the store of value itself, the point and purpose of value, the thing we pursued for its own sake.

This shift was accepted because it appeared logical, even sensible. It seemed like common sense. Yet in reality, it was the easy option – the lazy option – and it became the pivot point that set humanity on a path that would eventually lead us away from ourselves.

What few people have ever recognised – and fewer still have been willing to challenge – is that once money became the centre of value, our focus shifted away from people and the human experience. Instead, we became fixated on money itself, and then on the power, position, control, and influence that money could buy.

Human life became stratified by how much or how little of it we possessed. Success became synonymous with wealth. Poverty became synonymous with failure. And the human experience was reduced to a spectrum between rich and poor.

Over time, this became normalised. Wealth and poverty have existed for so long, in so many forms and nuances, that most people accept the wealth divide as a natural feature of life. Many even believe it is acceptable – that some should thrive while others go without, that some should have more than they could ever need while others struggle to meet the basics of life.

The dynamic has only worsened. The transition from feudalism to industrialisation was celebrated as progress, but the underlying imbalance remained. The gap between those who have and those who have not continued to widen. Eventually, it reached a point where no rule, regulation, or law could meaningfully correct it. The imbalance had become embedded in the system itself.

And as always, more wants more. The existence of social classes, and the aspiration to climb them, was never enough.

A point came when the elites – those who already held power – realised that if they wanted to accumulate even more, they would have to change the rules of the game. And who was there to stop them? They already controlled everything.

People talk endlessly about new world orders, Fabianism, the WEF, and other groups. But regardless of the motivations or the plans behind these movements and those who run and influence any government, the reality is simple: any value system has a finite total value within it, even if it grows. That value moves depending on the actions – whatever the motivation and whether conscious or unconscious – of those who control the system.

Under a ring‑fenced money system, such as the gold standard, no new money can be created. The total value is fixed. Even if the scales of wealth are pushed to their limits, the wealthy cannot accumulate beyond the system’s natural ceiling. They can own a lot, but they cannot conjure the value out of thin air that would enable the few to own and control everything.

This system – flawed as it most certainly was – remained in place until 1971. And only when we understand what changed in that moment can we understand what has happened to us since.

The creation of the fiat money system, which allowed those in control to create money at will, enabled the greatest transfer of wealth in human history. It allowed the already wealthy to become unimaginably wealthier by creating money that could then be used to buy everything of real value – businesses, infrastructure, land, resources, and the essentials of community life.

Ownership and power were transferred to people who could never have acquired them under a value system grounded in reality. The new system was built on methods that were dishonest and fundamentally false.

Ordinary people didn’t question it. Why would they? Their value system – money – still looked the same. A pound was still a pound. A dollar was still a dollar. But the reality had changed completely.

This is why life today looks so different from life 60 or 70 years ago. There are anomalies everywhere. A single average wage once supported a family, bought a home, and provided security. Today, even the national minimum wage is not enough for one person to survive without benefits, charity, or debt.

Because money is the centre of value, people have been conditioned to believe that if they have what they want, everything is fine. So the consequences of the fiat system – what it has done to people, communities, and the environment – have not been treated as the priority they should have been.

The West has been told that the last 80 years have been peaceful, that there are no real problems ahead, and that nothing fundamental could ever change. Meanwhile, laws, working practices, and – most importantly – technology have changed at an accelerating pace. Everything has changed while we believed we were standing still.

We can see clearly what the Industrial Revolution did. We understand why the labour movement emerged. Industrialisation devalued human effort by replacing or reducing the need for human labour with machines wherever it could be done.

Yet we have failed to notice the evolution happening beneath our feet today. People believe the world still works as it did after the Second World War. Very few see the catastrophe unfolding around us: the next great technological shift – the rise and takeover of AI.

Just as people once accepted that machines would replace or reduce the need for manual labour, many now accept that AI will replace cognitive labour. And they assume this means nobody will have to work.

There is a dangerous collective assumption that technology has been created for the betterment of humanity. But the reality is that modern technology – especially AI – has been developed for profit and control, not for helping and supporting humanity.

If it had been created to improve life, we would already be living in a world where even the poorest had enough, where jobs were secure, and where technology enhanced life rather than replacing it.

Instead, we are living through a neoliberal, globalist model powered by fiat money – a model that extracts value from people and concentrates it in the hands of a few.

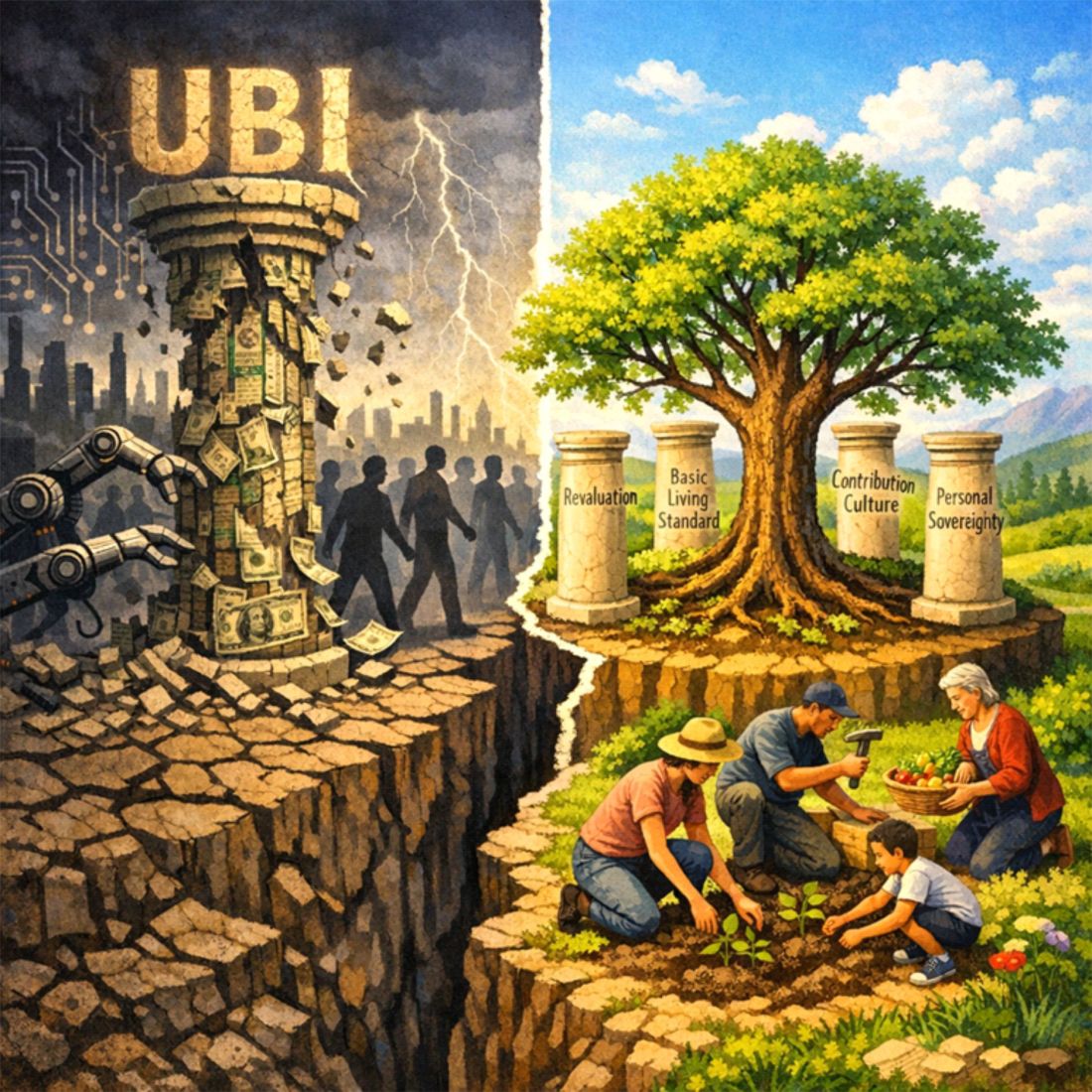

Even the architects of this system know it cannot work. That is why figures like Sam Altman now promote UBI – Universal Basic Income – as the supposed solution, for the fast-approaching time when for growing numbers, there will no longer be any kind of work.

The Fiat Era, AI, and the False Promise of UBI

UBI has been tested in small‑scale trials around the world. The idea is simple: everyone receives a set amount of income, regardless of what they do. It is appealing because it promises security in a world where jobs are disappearing. It reassures people that even if AI replaces their work, they will still be able to live the life they know today.

But this belief rests on a dangerous misunderstanding.

People assume UBI means they will continue to live as they do now – with the same homes, the same comforts, the same access to goods and services – simply without needing to work. They imagine a world where machines do everything, and humans simply enjoy the benefits.

This is fantasy.

UBI, in the context of the system we have today, is idealism built on a lie. It assumes that money can be endlessly created to pay off debts that already represent money that does not exist. It assumes that the system can continue functioning even as the economic role of billions of people disappears. It assumes that those who own everything will willingly fund the lives of those who own nothing.

The technological revolution – and the speed at which it has unfolded – was only possible because of the fiat money system. A system that survives only because enough people still believe in it. A system where most people already own nothing, and where the underlying structure is already broken.

The people who own everything – the corporations, the financial institutions, the elites who control the levers of power – cannot run a world where machines do all the work and billions of people contribute nothing.

The equation does not balance.

A system where everyone takes but no one contributes cannot function.

UBI is simply a tool to maintain the illusion that money still matters, that the system still works, and that people still need the very system that is failing them.

If we continue removing jobs at the current rate, a point will come – soon – when people outside the protected classes will have no means to survive. Not because they lack ability. Not because they lack willingness. But because the system will no longer have a place for them.

The question is not whether technology is good or bad. Technology can be used to advance humanity. But the reality we face is that AI has been developed to remove human involvement, not to improve human life. It has been built to maximise profit, minimise cost, and eliminate the “problem” of human labour.

And this is where the truth becomes unavoidable:

UBI will not save us.

It cannot save us.

It was never designed to.

UBI is the last tool of a dying system – a sticking plaster on a wound that requires surgery. It is the final illusion offered by a worldview that has already collapsed under its own contradictions.

The dam is cracking.

The pressure is rising.

And UBI cannot hold it back.

There is another way – a way of living that embraces technology without using it to replace or devalue people. A way built on local economies and local governance, with the Basic Living Standard at its heart. A way that restores human value, dignity, and sovereignty.

A time is approaching – sooner than most realise – when we will have to choose. We can continue sleepwalking down the path we are on, a path controlled by a few, where most will find neither benefit nor happiness. Or we can choose to walk a different way – a way where each of us contributes, participates, and lives with genuine freedom and sovereignty.

The alternative may flatten hierarchies, decentralise power, and remove the obscene concentrations of wealth that exist today. But it will also create lives worth living – lives grounded in peace, purpose, and the true human value that comes from within us, not from the money system that has defined us for far too long.

The Turning Point: Why UBI Cannot Save a Collapsing System

UBI is being sold as a compassionate solution, a stabiliser, a safety net for a world without work. But the truth is far more uncomfortable:

UBI is the final illusion of a system that has already collapsed in every meaningful way.

It is the last tool available to a worldview that cannot admit its own failure. It is the final attempt to preserve a structure that has been unravelling for decades – a structure built on false value, false scarcity, false growth, and false promises.

The destruction of jobs was not an accident.

It was not an unfortunate by‑product of progress.

It was a deliberate choice – a choice made by those who benefit from a world where human beings are no longer required.

The system has been moving toward this point for generations:

- first by replacing physical labour with machines

- then by replacing skilled labour with automation

- now by replacing cognitive labour with AI

At each stage, the justification was the same: progress.

At each stage, the consequences were the same: displacement.

At each stage, the winners were the same: those who already held power.

And now, as the final stage unfolds, the system has run out of excuses – and out of time.

The truth is simple:

A society built on money cannot survive when people no longer earn it.

A society built on work cannot survive when people no longer have it.

A society built on consumption cannot survive when people cannot afford to consume.

UBI does not solve this.

It cannot solve this.

It was never designed to solve this.

UBI is a sedative – a way to keep people calm while the system collapses around them. It is a way to delay the moment when the public realises that the world they were promised no longer exists.

But the dam is cracking.

The pressure is rising.

And UBI cannot hold it back.

A world where billions of people have no economic role is not a world that can be stabilised with monthly payments.

It is a world that requires a complete rethinking of value, contribution, governance, and the purpose of human life.

And that is where the real alternative begins.

The Alternative: A System That Solves the Root Causes

If UBI is the last illusion of a dying system, then the question becomes unavoidable:

What replaces it?

Not a reform.

Not a patch.

Not a new policy within the old worldview.

What replaces it must be a new operating system for society – one that addresses the root causes of the crisis, not the symptoms. One that works with human nature, not against it. One that restores dignity, purpose, and sovereignty to every person.

That system exists.

It is called the Local Economy & Governance System (LEGS), and it is built on four pillars:

- The Revaluation

- The Basic Living Standard

- The Contribution Culture

- Personal Sovereignty

Together, they form a coherent, humane, practical alternative to the collapsing money-centric world.

1. The Revaluation: Changing What We Value

The crisis we face did not begin with fiat money.

It did not begin with globalisation.

It did not begin with AI.

It began with a value system that placed money above people.

The Revaluation is the shift from:

Money-centric value → human centric value

It is the moment we stop measuring life through:

- price

- profit

- productivity

- accumulation

and begin measuring it through:

- wellbeing

- contribution

- community

- dignity

- sustainability

- fairness

Without this shift, nothing else can work.

With it, everything else becomes possible.

2. The Basic Living Standard: Security as a Universal Right

The Basic Living Standard (BLS) is not UBI.

It is not a handout.

It is not dependency.

It is a guarantee that every person can meet their essential needs – food, shelter, energy, water, healthcare, and participation – from a normal week’s contribution.

It breaks the link between survival and employment.

It removes fear, insecurity, and dependency.

It ensures that no one can fall below the basics of life.

And unlike UBI, it is not funded by printing money or taxing a collapsing economy.

It is built into the structure of the local economy itself.

The BLS is the economic foundation of a people‑first society.

3. The Contribution Culture: Work as Meaning, Not Survival

The Contribution Culture replaces the toxic idea that:

“If you don’t work, you don’t deserve to live.”

with:

“Everyone who can contribute, contributes – because contribution is meaningful, valued, and secure.”

In a Contribution Culture:

- work is not coerced

- work is not a punishment

- work is not a transaction

- work is not a competition

- work is not a fight for survival

Work becomes:

- participation

- purpose

- community

- shared responsibility

- a source of dignity

This is the cultural foundation of the alternative – and the antidote to the crisis of work in an AI‑dominated world.

4. LEGS: The Local Economy & Governance System

LEGS is the structural foundation – the practical framework that makes the Revaluation, the BLS, and the Contribution Culture real.

It is built on:

- local economies

- local food systems

- local governance

- participatory democracy

- shared responsibility

- transparency

- decentralisation

LEGS solves the problems that have existed since long before fiat:

- centralised power

- hierarchical control

- distance between decision‑makers and consequences

- systems that cannot see the ground

- economies that treat people as units

- governance that manages people instead of serving them

And it solves the problems that fiat accelerated:

- extraction

- inequality

- speculation

- debt dependency

- the illusion of infinite value

And it solves the problems that AI will make catastrophic:

- the removal of jobs

- the collapse of income

- the loss of agency

- the erosion of sovereignty

- the concentration of power in the hands of a few

LEGS is not a policy.

It is a new operating system for society.

5. Personal Sovereignty: The Human Foundation

Personal sovereignty is the right – and responsibility – of every individual to live as a free, ethical, self‑directed human being.

It is protected through:

- security

- transparency

- locality

- shared responsibility

- meaningful contribution

The money-centric system destroys sovereignty by creating dependency through UBI.

LEGS restores sovereignty by creating participation.

Why LEGS Works Where UBI Cannot

UBI tries to preserve the old system.

LEGS replaces it.

UBI depends on money.

LEGS depends on contribution.

UBI centralises power.

LEGS decentralises it.

UBI treats people as passive recipients.

LEGS treats people as active participants.

UBI assumes scarcity.

LEGS builds natural abundance.

UBI keeps people dependent.

LEGS restores personal sovereignty.

UBI is temporary.

LEGS is sustainable.

UBI is the illusion of security.

LEGS is the reality of it.

The Choice Ahead

Humanity is approaching a moment where the old system will no longer function – not because of fiat, not because of politics, but because AI will remove the economic role of billions of people.

UBI cannot solve this.

It was never meant to.

The only real alternative is a system that:

- restores human value

- guarantees security

- redefines work

- decentralises power

- rebuilds community

- and places people first in every sense

That system exists.

It is coherent.

It is humane.

It is practical.

It is necessary.

It is the Local Economy & Governance System, built on the Basic Living Standard, the Contribution Culture, and the Revaluation.

This is not a dream.

It is not a theory.

It is not a utopia.

It is the only path that deals with the root causes – not just the symptoms – of the unravelling we are living through.

And the time to choose it is now.

Further Reading:

1. An Overview of a People-First Society

https://adamtugwell.blog/2026/01/03/an-overview-of-a-people-first-society/

Why it’s critical: This article lays out the philosophical foundation for a people-centric society, directly addressing the shift away from money-centric values. It’s essential for grasping the big-picture vision that underpins all other proposals in this document.

2. The Local Economy & Governance System (LEGS): Online Text

https://adamtugwell.blog/2025/11/21/the-local-economy-governance-system-online-text/

Why it’s critical: This is the definitive resource on LEGS, the proposed alternative to the money-centric system that may soon look to UBI. It explains the system’s structure, principles, and practical mechanisms for replacing the current economic model. If you want to understand the practical solution, start here.

3. The Basic Living Standard: Explained

https://adamtugwell.blog/2025/10/24/the-basic-living-standard-explained/

Why it’s critical: This article clarifies the concept of the Basic Living Standard (BLS), a cornerstone of the LEGS system. It distinguishes BLS from UBI and explains why it’s a more sustainable and empowering approach.

4. The Contribution Culture: Transforming Work, Business, and Governance for Our Local Future with LEGS

https://adamtugwell.blog/2025/12/30/the-contribution-culture-transforming-work-business-and-governance-for-our-local-future-with-legs/

Why it’s critical: This article explores how LEGS redefines work and contribution, moving away from survival-based employment to meaningful participation. It’s vital for understanding the cultural transformation needed for the new system to succeed.

5. The Local Economy Governance System (LEGS): Escaping the AI Takeover and Building a Human Future

https://adamtugwell.blog/2025/12/04/the-local-economy-governance-system-legs-escaping-the-ai-takeover-and-building-a-human-future/

Why it’s critical: This piece directly addresses the impact of AI on work and society, and how LEGS offers a human-centred response to technological disruption. It’s especially relevant for readers concerned about the future of employment.

Why These Are Critical

These articles collectively provide:

- The philosophical rationale for change.

- A detailed blueprint for the proposed alternative system.

- Clear explanations of the foundational concepts (BLS and Contribution Culture).

- Direct responses to the challenges posed by AI and the collapse of traditional work.