It’s been quite a week for Reform, and without the current political backdrop, the events unfolding could have been enough to suggest that the evolution of the Reform project would grind to a halt – no matter what came next.

Until now, the party – new in name only – has been riding high in the polls, cultivating the appearance of a government‑in‑waiting that could do no wrong. Their greatest advantage has been simple: unlike Labour, the Conservatives or the Liberal Democrats, Reform has not yet been involved in creating the problems that have brought the country to its knees.

For many voters, that alone has been enough. It’s why so many have been willing to overlook the party’s patchy record in local government since taking over a number of councils last May.

But for others, things have never been so straightforward. A growing list of unsettling questions has followed the current party of Nigel Farage, particularly around its fixation on grand, US‑style DOGE ‘solutions’ and other plans for the future such as parachuting in business‑world advisers to take charge where they already recognise that inexperienced politicians cannot.

These announcements may sound impressive to a disillusioned electorate, but – like the words and policies of every government in recent living memory – they tend to obscure reality rather than confront it head on.

The name “Reform” has always been a question in itself. But its evolution is even more important to consider now, given its position on the political right.

Reform was born of the Brexit Party, which was itself born of UKIP (the pre‑2016, EU Referendum version), which itself emerged from the often‑forgotten Anti‑Federalist League.

Many of the same people have moved through each iteration. And while today’s Reform claims to draw support from across the political spectrum, its origins lie firmly in the fissures of the Conservative Party. Cracks visible since the time of Heath, that widened after Thatcher’s departure and during Major’s distinctly EU-phile premiership.

What began as an anti‑EU movement became a home for many disenfranchised Conservatives – including Farage himself. However, beyond the anti‑EU narrative that he and others have pushed so effectively, there has never been much inclination to challenge how the system itself works when you get into the mechanics of how everything really functions and who it all serves.

Those who have watched closely – the language, the policies, the motivations, the hands being shaken – could always see that “Reform” risked being a deeply misleading name.

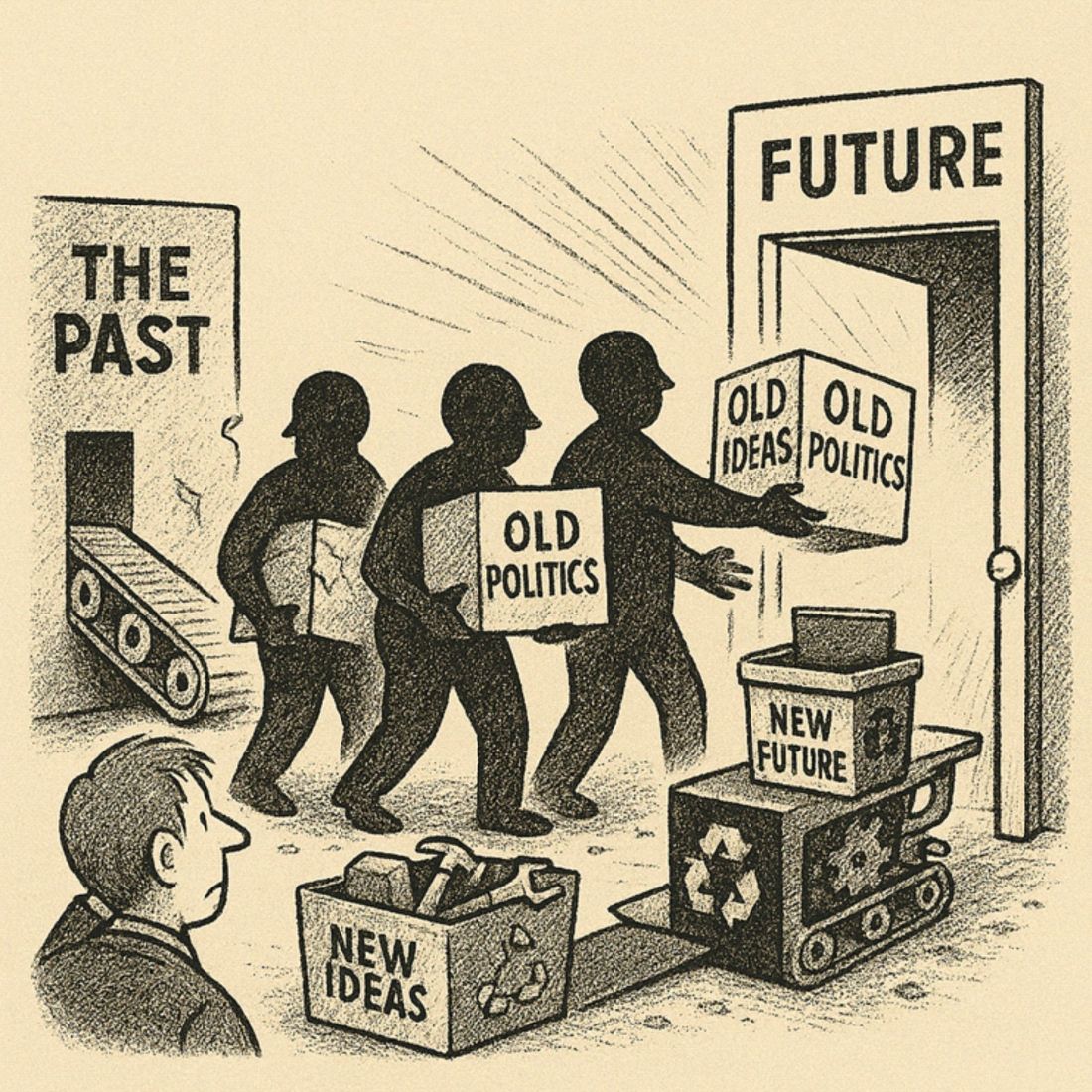

Instead of providing inspiration and genuine reason for hope, each new development has instead reinforced the fear that this movement is less about genuine reform and more about resetting the same establishment machinery under a different banner – essentially being about preserving everything in our system of economics and governance that is fundamentally wrong and doing the most harm.

So, when Laila Cunningham was announced as the London mayoral candidate a few days ago, there was reason to wonder if this might be the moment something changed – and be a sign that Reform could still recalibrate and chart a different course. However, within days, the party took a massive and arguably defining leap backwards, confirming once again that any hopes for the moment were misplaced and those ongoing concerns have been right all along.

Nadhim Zahawi’s defection from the Conservatives – bringing with him a pile of political baggage symbolising everything wrong with not just the Tories but the entire political class – was the moment any germinating bubble burst.

The shift in messaging across the media landscape was also immediate. And anyone at Reform HQ would have done well to heed the sudden change in tone emerging from sources that had previously been supportive to them that sat outside the echo chamber of dedicated ‘reformists’ who still believe that Farage’s machine is capable of doing no wrong.

Then came Robert Jenrick. His “sacking” and expulsion from the Conservatives morphed into a full Reform defection in under six hours yesterday.

Like Zahawi, Jenrick was deeply embedded in everything the Johnson and Sunak governments were about. And the circumstances and emerging detail of his departure suggest a politician looking backwards to more of where we have already been; not forwards, as few outside politics really doubt will need to be the direction of travel – built on a definable break with and departure from the past.

Reform now faces a critical question: with its growing (re)alignment to establishment figures and money‑centric politics, is it just becoming a reformed version of the very party that it was ostensibly re-formed to replace?

The identity crisis within conservatism and the political right that has existed since the days of the Common Market – now seems to be reappearing within Reform. And with each defection eagerly embraced by Farage, and in ways that suggest they were always part of the very same machine, just with different interpretations of how it should work, the chance of a genuinely different future emerging from the right appears to be quickly slipping away.

In the end, it all comes back to the same unavoidable truth:

You cannot build the future with the architects of the past.

Reform’s recruitment strategy signals a retreat into old habits, and their words and policies suggest they will either fall into line with the current establishment trajectory or simply trash whatever remains after Labour has finished with it – IF they take power after the General Election takes place – as many people desperate for change still hope they will do.

Regrettably, those tired and bewildered people who believe they are the answer may not see it or wish to accept it, but Reform, Reconservatives, Reformatives, ReCons, Conservatives 2.0, or whatever they really are in their current form isn’t what the UK or anyone genuinely need.

There is nothing about them that suggests that they are willing, able or indeed ready to deliver on behalf of us all.

Boldness and clarity are essential for building a better future. Not a thickening cloud of uncertainty, pinned by figures from the past that people looking forward know it would be much healthier to leave behind.