“Locality is the natural scale of human life. Everything else is a managed simulation.”

A Note from Adam

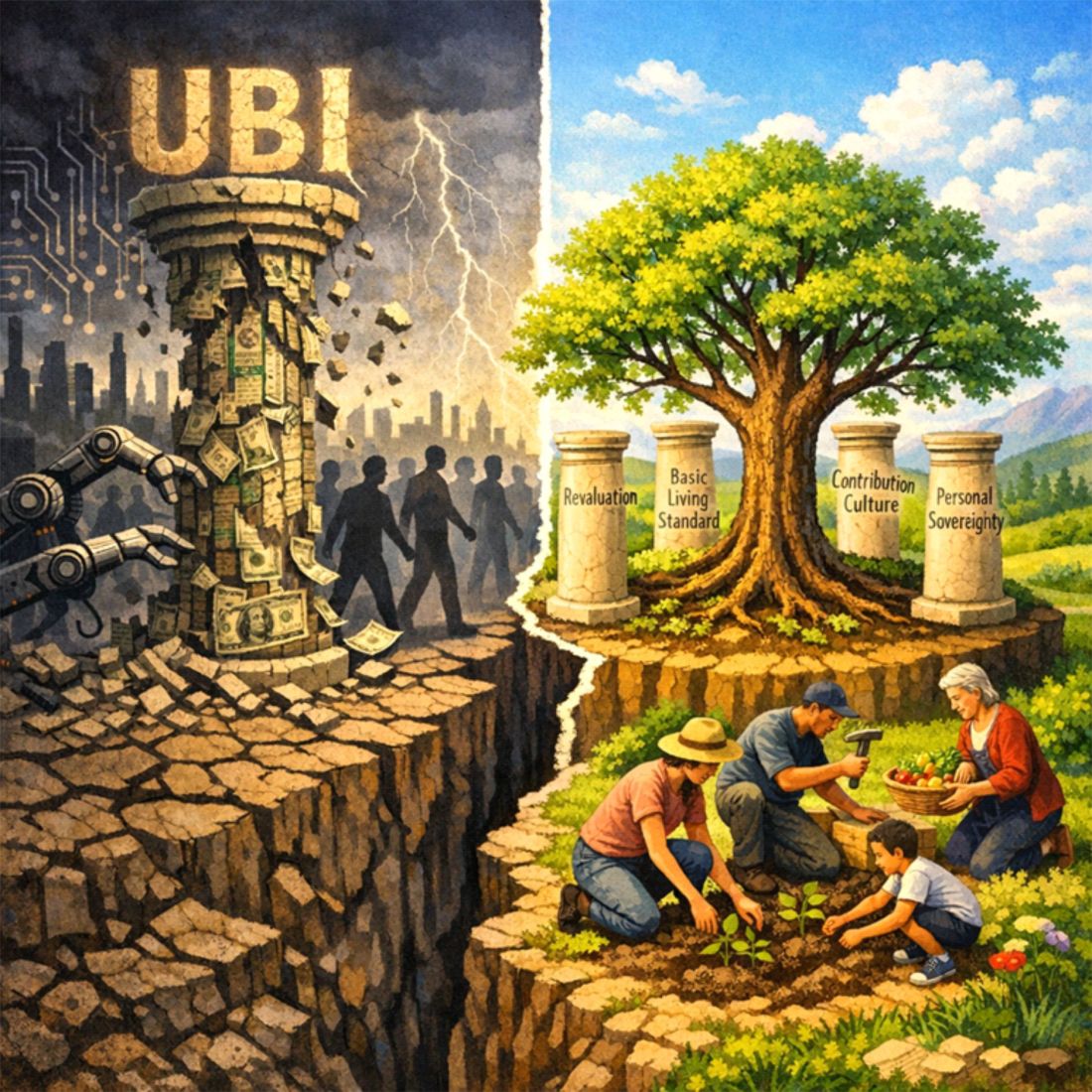

This essay sits within a wider body of work that includes The Local Economy & Governance System, The Basic Living Standard, The Revaluation, The Contribution Culture, Foods We Can Trust – A Blueprint’ and Centralisation Only Rewards Those at the Centre.

All of these pieces are attempts to describe something that should be obvious, but has become strangely difficult to see: that the world we live in today is not built on real life, but on layers of abstraction that have replaced it.

The tragedy – and the reason this work is necessary – is that when people are raised inside an abstract world, the real world begins to look abstract.

Locality looks naïve.

Community looks unrealistic.

Contribution looks idealistic.

Real food looks nostalgic.

Real governance looks impossible.

Real value looks imaginary.

Real life looks like a fantasy.

This inversion is not accidental. It is the predictable outcome of a system that has normalised distance, centralisation, and money as the organising principles of life.

When the abstract becomes normal, the real becomes suspicious.

People reject the very things that would make them healthy, grounded, connected, and free – not because they are wrong, but because they have been conditioned to believe that the real is impractical, inefficient, or outdated.

This rejection is not a rational act. It is a form of self‑harm.

It is the moment when a person turns away from the only scale of life that can sustain them – the local, the human, the grounded – and chooses instead the familiar discomfort of the abstract world.

This essay is written to break that spell.

It is written to help people see the abstract world clearly, perhaps for the first time.

It is written to show how the real world has been hidden in plain sight.

It is written to reveal why the real feels abstract, and why the abstract feels real.

It is written to open the doorway back to a life that makes sense.

If the ideas inside this essay feel unfamiliar, strange, or even unsettling, that is not a sign that they are wrong. It is a sign of how deeply the abstract world has shaped our perception.

The work that follows – including LEGS, the Basic Living Standard, and the wider architecture of a local, human or people-first economy – is not an attempt to invent a new world.

It is an attempt to return to the only world that has ever truly worked.

A world where life is lived at the scale of human beings.

A world where value is real.

A world where community is lived.

A world where food is understood.

A world where governance is accountable.

A world where health is natural.

A world where meaning is visible.

A world where people are whole.

This essay is the beginning of that return.

Stepping Out of the Abstract: Why This Essay Exists

We live in a world where almost everything that matters has been lifted out of daily life and placed somewhere distant, managed by people we never meet, shaped by systems we never see, and justified by narratives we never question.

This distance has become so normal that most people no longer recognise it as distance at all.

They mistake abstraction for reality because they have never known anything else.

This is the quiet tragedy of the money‑centric, centralised world:

When you are raised inside the abstract, the real begins to look abstract.

Locality – the natural scale of human life – begins to feel naïve.

Community begins to feel unrealistic.

Contribution begins to feel idealistic.

Real food begins to feel nostalgic.

Real governance begins to feel impossible.

Real value begins to feel imaginary.

And because the abstract world is all we have been shown, many people reject the real world when they first encounter it – not because it is wrong, but because it feels unfamiliar.

This rejection is not a failure of intelligence.

It is a consequence of conditioning.

It is also a form of self‑harm.

Because the real world – the local, the human, the grounded – is the only place where health, meaning, agency, and freedom can genuinely exist.

This essay is written for the moment when people begin to sense that something is wrong, even if they cannot yet name it.

It is written for the moment when the abstract world stops feeling natural.

It is written for the moment when the doorway to the real world becomes visible – even if only faintly.

It draws on the wider body of work – including Centralisation Only Rewards Those at the Centre – to show how the abstract world hides in plain sight, how it shapes our behaviour without our consent, and how it convinces us to reject the very things that would make our lives whole again.

This essay is not an argument.

It is an invitation.

An invitation to see clearly.

An invitation to understand deeply.

An invitation to step back into the real.

SECTION 1 – Life Inside the Abstract

Most people can feel that something is wrong with the world today, even if they can’t quite name it. There is a sense of disconnection running through everything – work, community, politics, food, even our relationship with ourselves.

Life feels harder than it should be. Nothing seems to add up. And yet, when we look around, the structures that shape our lives appear normal, familiar, even inevitable.

The truth is far more uncomfortable.

We are not living real lives anymore.

We are living in an abstract world – a world built on systems, narratives, and mechanisms that sit outside our direct experience, yet govern almost every part of it.

We have been conditioned to treat these abstractions as reality, even when they bear no resemblance to the lives we actually live.

We mistake the abstract for the real because we have forgotten what real life feels like.

Real life is local.

Real life is human.

Real life is experienced directly – through people, places, relationships, and the natural world.

But the world we inhabit today is mediated through layers of distance, bureaucracy, digital interfaces, centralised systems, and economic structures that most of us never see.

We live inside a world of processes we do not control, rules we did not write, and decisions made by people we will never meet.

We have been taught to believe that this is normal.

It isn’t.

It is simply the result of a system that has replaced lived experience with abstraction – and then convinced us that the abstraction is real.

This is why so many people feel exhausted, anxious, or powerless. It is why work feels meaningless. It is why communities feel hollow. It is why food feels fragile. It is why politics feels distant. It is why life feels precarious.

We are trying to live real lives inside an abstract world.

And the abstract world is collapsing.

To understand why – and to understand the alternative – we must first see the architecture of the abstract world clearly. Because once you see it, you cannot unsee it. And once you understand how abstraction has replaced reality, you begin to understand why the only real solution is to return life to the scale where humans actually exist.

That scale is the local.

And the system that makes that return possible is the Local Economy & Governance System (LEGS).

But before we can reach that point, we must first understand how the abstract world was built – and why it has taken us so far away from the lives we were meant to live.

SECTION 2 – How Abstraction Shapes Daily Life

One of the most important things we have to recognise – and perhaps the hardest – is just how much of the world we take for granted without ever questioning how it really works.

We assume that because something is familiar, it must also be real. We assume that because something is normal, it must also be natural. And we assume that because something has always been presented to us in a certain way, that way must be the truth.

But much of what we now treat as “real life” is nothing of the sort.

We are living in an abstract world – a world built on ideas, systems, and processes that sit far outside our direct experience, yet shape almost everything we do. And because these abstractions have been with us for so long, we rarely notice them. They hide in plain sight, precisely because we have stopped looking for anything else.

Food is the clearest example.

Recently, the website Farming UK asked whether food production and farming should be compulsory in schools. On the surface, it sounds like a sensible suggestion. Many people – especially those who live rurally – instinctively feel that children should understand where food comes from, how it is grown, and why it matters.

But the question itself reveals something much deeper.

Because we already have compulsory subjects in schools.

And yet almost none of them connect children to real life.

They are taught in the abstract.

They are delivered through textbooks, screens, worksheets, and exam specifications – not through lived experience. Children learn about the world through representations of the world, not through the world itself. They learn about life without ever touching life.

So when we say “make food education compulsory,” we are really saying “add food to the list of things we teach abstractly.”

We don’t even notice the contradiction.

We don’t notice that the very structure of schooling has become abstract – detached from the realities of life, detached from the skills that sustain us, detached from the communities we live in. We don’t notice that the way we teach children about the world is itself part of the problem.

We don’t notice because abstraction has become normal.

We have been conditioned to believe that learning happens in classrooms, not in fields, kitchens, workshops, or communities.

We have been conditioned to believe that knowledge comes from institutions, not from experience.

We have been conditioned to believe that the abstract version of life is the real one – and that the real one is somehow outdated, inefficient, or unnecessary.

This is how deeply the abstract world has embedded itself.

We no longer see the distance between the representation and the reality.

We no longer see the gap between what we are taught and what we need.

We no longer see that the systems we rely on are not built around life at all.

Food education is just one example – but it is the example that exposes the whole pattern.

Because food is not abstract.

Food is life.

Food is local.

Food is real.

And yet most people now understand food only through the abstract lens of supermarkets, supply chains, packaging, and price labels.

They understand food as something they buy, not something they grow, prepare, preserve, or share.

They understand food as a product, not a relationship.

So when we talk about teaching food in schools, we are really talking about teaching the abstract version of food – the version that fits neatly into a curriculum, not the version that sustains life.

This is the heart of the problem.

We are trying to fix the consequences of abstraction by adding more abstraction.

We are trying to reconnect people to real life through systems that are themselves disconnected from real life.

We are trying to solve a problem we have not yet recognised.

Because the problem is not that children don’t understand food.

The problem is that children – and adults – no longer live in a world where real life is visible.

We live in the abstract.

We think in the abstract.

We learn in the abstract.

We work in the abstract.

We eat in the abstract.

We govern in the abstract.

And because abstraction has become normal, we no longer see what it has taken from us.

But once you begin to see it – once you notice how much of life has been lifted out of reality and placed into distant systems – you begin to understand why so much feels wrong, disconnected, or hollow.

You begin to understand why the sums no longer add up.

You begin to understand why people feel lost.

You begin to understand why communities feel empty.

You begin to understand why the world feels fragile.

And you begin to understand why the only real solution is to return life to the scale where it actually exists.

The local.

The human.

The real.

SECTION 3 – Food: The Evidence for Local Reality

If there is one place where the difference between real life and the abstract world becomes impossible to ignore, it is food. Food exposes the truth that sits beneath everything else:

Local is real.

Local is healthy.

Local is human.

Abstract is false.

Abstract is unhealthy.

Abstract is dehumanising.

Food shows us this more clearly than anything else because food cannot be understood in the abstract. You cannot learn food from a worksheet. You cannot respect food from a PowerPoint. You cannot understand food from a supermarket shelf.

Food is something you learn by living with it.

For most of human history, food was part of daily life. Children didn’t need lessons about food – they absorbed it simply by being present.

They saw seeds planted, animals cared for, bread made, meals prepared, leftovers preserved, and seasons change.

They learned respect for food because they saw the work, the patience, the skill, and the care that food requires.

Food was not a subject.

Food was a relationship.

Food was real.

And because food was real, it made life real.

It grounded people physically, mentally, emotionally, and socially. It connected them to nature, to community, and to themselves.

This is what locality does.

Locality makes life real.

Locality makes life healthy.

But today, food has been lifted out of daily life and placed into the abstract.

Most people no longer grow food.

Most people no longer prepare food from scratch.

Most people no longer understand where food comes from or what it takes to produce it.

Instead, food arrives through a system that is distant, centralised, and invisible. We experience food through packaging, branding, supply chains, and price labels. We “know” food only as something we buy – not something we understand.

And because food has become abstract, our relationship with life has become abstract.

We no longer see the soil.

We no longer see the seasons.

We no longer see the labour.

We no longer see the community.

We no longer see the meaning.

We see only the abstraction – and we mistake it for reality.

This is why the suggestion that food production should be compulsory in schools misses the point so completely. It assumes that the problem is lack of information. It assumes that the solution is more teaching. It assumes that adding food to the curriculum will reconnect children to real life.

But compulsory subjects are already taught in the abstract.

They are delivered through screens, worksheets, and exam specifications – not through lived experience. They are disconnected from the world they claim to describe. They teach children about life without ever letting them touch life.

So when we say “teach food in schools,” we are really saying “teach the abstract version of food.”

We don’t even notice the contradiction because abstraction has become normal.

But food refuses to be abstract.

Food exposes the lie.

Food reveals the truth.

Because food can only be understood locally.

Food can only be respected locally.

Food can only be lived locally.

And when food is local, life becomes local.

When food is real, life becomes real.

When food is part of daily life, people become grounded, connected, and healthy – physically and mentally.

This is the deeper truth hiding in plain sight:

Anything that is real must be lived locally.

Anything that is abstract becomes unhealthy – for people, for communities, and for the world.

Food shows us this with absolute clarity.

When food is local, people are independent.

When food is local, communities are resilient.

When food is local, life makes sense.

But when food becomes abstract, people become dependent.

Communities become hollow.

Skills disappear.

Respect disappears.

Meaning disappears.

Health – physical and mental – declines.

Food is the proof that abstraction is not just a philosophical idea.

It is a lived experience with real consequences.

And it is also the proof that the way back to a healthy, grounded, human life is through locality.

Because food cannot be centralised without becoming abstract. And life cannot be centralised without becoming abstract.

Food shows us the truth we have forgotten:

Local is real.

Local is healthy.

Abstract is false.

Abstract is unhealthy.

And once you see this in food, you begin to see it everywhere.

SECTION 4 – When Abstraction Disrupts Meaning

Once you begin to see how food reveals the difference between the real and the abstract, something else becomes clear: the reason so much of life feels confusing, unstable, or unhealthy today is because we are trying to live real lives inside systems that are not real.

When life is local, it is grounded.

When life is local, it is human.

When life is local, it makes sense.

But when life becomes abstract, it becomes distorted.

It becomes stressful.

It becomes unhealthy – physically, mentally, emotionally, socially.

And because abstraction has become normal, we rarely connect the dots.

We feel the symptoms, but we don’t see the cause.

We feel overwhelmed, but we don’t see the distance that created it.

We feel powerless, but we don’t see the systems that removed our agency.

We feel disconnected, but we don’t see how far we’ve been pulled from real life.

We feel anxious, but we don’t see that the world we live in is built on instability.

We feel lost, but we don’t see that the map we were given was abstract all along.

Food shows us this clearly.

When food was part of daily life, people understood the world around them. They understood seasons, weather, soil, animals, and the rhythms of nature. They understood effort, patience, and consequence. They understood community, because food required community.

This understanding created stability – not just physical stability, but mental and emotional stability too.

Locality grounds people.

Locality gives life shape.

Locality gives life meaning.

But when food becomes abstract, that grounding disappears.

People no longer understand the rhythms of life.

They no longer see the connection between effort and outcome.

They no longer experience the satisfaction of contribution.

They no longer feel part of anything bigger than themselves.

They no longer feel capable of providing for themselves.

This creates a deep, quiet anxiety – the kind that sits beneath everything else.

Because when the most essential part of life becomes abstract, everything else becomes abstract too.

Work becomes abstract – disconnected from purpose.

Community becomes abstract – disconnected from place.

Governance becomes abstract – disconnected from people.

Value becomes abstract – disconnected from meaning.

Identity becomes abstract – disconnected from reality.

And when everything becomes abstract, life stops making sense.

People feel like they are constantly running but never arriving.

They feel like they are constantly working but never secure.

They feel like they are constantly consuming but never satisfied.

They feel like they are constantly connected but never seen.

They feel like they are constantly informed but never understanding.

This is not a personal failing. It is the predictable outcome of living in a world that has replaced reality with abstraction.

A world where:

- food is a product, not a relationship

- work is a transaction, not a contribution

- community is a slogan, not a lived experience

- governance is a bureaucracy, not a responsibility

- value is a price tag, not a truth

- identity is a profile, not a person

A world where the things that should be local – food, work, community, governance, meaning – have been centralised, standardised, and abstracted.

A world where the things that should be lived have been turned into things that are managed.

A world where the things that should be experienced have been turned into things that are consumed.

A world where the things that should be human have been turned into things that are economic.

And because this world is abstract, it is unhealthy.

It is unhealthy for bodies.

It is unhealthy for minds.

It is unhealthy for communities.

It is unhealthy for the environment.

It is unhealthy for democracy.

It is unhealthy for life.

Locality is not a lifestyle choice.

Locality is the natural scale of human existence.

When life is local, it becomes real again.

When life is local, it becomes healthy again.

When life is local, it becomes meaningful again.

Food shows us this.

Food proves this.

Food is the doorway into this understanding.

And once you see how food reveals the truth about locality and abstraction, you begin to see the deeper structure behind it – the mechanism that created the abstract world and keeps it in place.

That mechanism is centralisation.

And centralisation only ever rewards those at the centre.

SECTION 5 – How Centralisation Sustains Abstraction

Once you see how abstraction pulls life away from the local, the next questions become unavoidable:

Why has so much of life been lifted out of the local in the first place?

Who benefits from life becoming abstract?

And why does the system keep moving further away from the real?

The answer is centralisation.

Centralisation is not an accident. It is not a side‑effect. It is not an unfortunate by‑product of “modern life.”

Centralisation is the mechanism that makes the abstract world possible.

It is the structure that takes power, ownership, and decision‑making away from the local – away from the people who live with the consequences – and moves it upward, into the hands of those who benefit from distance.

And once you understand centralisation, you understand why the world feels the way it does.

Centralisation grows because abstraction feeds it

The money‑centric system we live in today is built on a simple equation:

Money → Wealth → Power → Control → Centralisation

Everyone understands the first step.

Even people with very little money know that money gives them more control over their own lives.

But as you move up the hierarchy, the dynamic changes.

Money no longer gives control over your own life – it gives control over other people’s lives.

And once that dynamic exists, centralisation becomes inevitable.

Because the more centralised a system becomes, the easier it is for those at the centre to extract value from everyone else.

Centralisation rewards the centre.

Abstraction hides the extraction.

Locality is the only thing that resists it.

This is why the system keeps pulling life away from the local.

Locality is real.

Locality is human.

Locality is healthy.

Locality is accountable.

And centralisation cannot survive in a world where people live real, local lives.

Centralisation always removes the local – and replaces it with the abstract

You can see this pattern everywhere once you know what to look for.

Food used to be local.

Now it is controlled by global supply chains, supermarket monopolies, and distant corporations.

Work used to be local.

Now it is shaped by national policy, global markets, and corporate structures that have no relationship to the communities they affect.

Governance used to be local.

Now decisions are made by people who will never meet those they govern.

Education used to be rooted in community life.

Now it is delivered through standardised curricula designed far away from the children they are meant to serve.

Health used to be grounded in local knowledge, local relationships, and local responsibility.

Now it is managed through centralised systems that treat people as data points.

In every case, the pattern is the same:

Centralisation removes life from the local and replaces it with the abstract.

And because abstraction is unhealthy – physically, mentally, socially, environmentally – centralisation always harms the people furthest from the centre.

Centralisation creates distance – and distance removes empathy

When decisions are made locally, they are made by people who see the consequences.

When decisions are made centrally, they are made by people who never do.

Distance removes empathy.

Distance removes accountability.

Distance removes humanity.

This is why centralised systems feel cold, bureaucratic, and indifferent.

It is not because the people inside them are bad.

It is because the structure itself removes the human connection that makes good decisions possible.

A policymaker in Westminster does not see the farmer whose livelihood is destroyed by a regulation.

A supermarket executive does not see the community that loses its last local shop.

A global corporation does not see the soil degraded by its supply chain.

A distant official does not see the child who never learns where food comes from.

Centralisation makes harm invisible – and therefore easy.

Centralisation is the opposite of locality – and the opposite of health

Locality is real.

Locality is grounding.

Locality is healthy.

Centralisation is abstract.

Centralisation is distancing.

Centralisation is unhealthy.

Locality connects people to life.

Centralisation disconnects people from life.

Locality builds resilience.

Centralisation creates fragility.

Locality builds community.

Centralisation creates dependency.

Locality builds understanding.

Centralisation creates confusion.

Locality builds meaning.

Centralisation creates emptiness.

Food shows us this more clearly than anything else.

When food is local, people are healthy – physically and mentally.

When food is abstract, people become dependent, disconnected, and unwell.

This is not a coincidence. It is the structure of the system.

Centralisation only rewards those at the centre

This is the truth that sits beneath everything:

Centralisation always rewards the centre and always harms the local.

It cannot do anything else.

Because centralisation is built on extraction – the extraction of wealth, power, autonomy, and meaning from the many to benefit the few.

And the only way to maintain that extraction is to keep life abstract.

Because abstraction hides the mechanism.

Abstraction hides the harm.

Abstraction hides the loss of agency.

Abstraction hides the loss of independence.

Abstraction hides the loss of community.

Abstraction hides the loss of health.

Once you see this, you understand why nothing will change until we stop living in the abstract and return life to the local.

And that is where the doorway opens.

Because if centralisation is the engine of the abstract world, then locality is the engine of the real one.

And LEGS is the structure that makes that return possible.

SECTION 6 – Locality: Where Life Becomes Real

Once you understand how abstraction pulls life away from the real, and how centralisation keeps everything abstract, the next truth becomes impossible to ignore:

Real life only exists at the local scale.

Everything else is a managed simulation.

This isn’t ideology.

It isn’t nostalgia.

It isn’t a romantic longing for the past.

It is simply how human beings work.

Locality is the natural scale of human life because it is the only scale where life can be experienced directly – through our senses, our relationships, our responsibilities, and our contributions.

Locality is where we see the consequences of our actions.

Locality is where we understand the world around us.

Locality is where we feel connected to something bigger than ourselves.

Locality is where we experience meaning.

Locality is where we experience health – physical, mental, emotional, social.

Locality is real.

Locality is grounding.

Locality is human.

Locality is healthy.

And food shows us this more clearly than anything else.

Food proves that locality is the natural scale of life

When food is local, it is part of daily life.

You see it.

You touch it.

You smell it.

You prepare it.

You share it.

You understand it.

Food becomes a relationship – not a product.

And because food is real, life becomes real.

People who live close to their food systems are more grounded, more resilient, more connected, and more mentally healthy.

They understand the rhythms of nature. They understand the value of effort. They understand the meaning of contribution. They understand the importance of community.

Local food systems create local understanding.

Local understanding creates local agency.

Local agency creates local resilience.

Local resilience creates local freedom.

This is why every healthy society in history has been rooted in locality.

Not because people were primitive.

Not because they lacked technology.

But because locality is the only scale where life can be lived fully.

Abstraction destroys the grounding that locality provides

When food becomes abstract, life becomes abstract.

People no longer understand the world around them.

They no longer feel connected to anything real.

They no longer feel capable of providing for themselves.

They no longer feel part of a community.

They no longer feel grounded in place.

They no longer feel secure.

This is why anxiety rises.

This is why depression rises.

This is why loneliness rises.

This is why communities fracture.

This is why people feel lost.

It is not because people have changed.

It is because the scale of life has changed.

We are trying to live human lives inside systems that are not human.

Locality restores what abstraction removes

When life returns to the local, everything changes.

People begin to feel connected again.

They begin to feel capable again.

They begin to feel responsible again.

They begin to feel valued again.

They begin to feel grounded again.

They begin to feel healthy again.

Locality restores:

- meaning

- agency

- contribution

- community

- resilience

- identity

- belonging

- stability

- health

Locality is not small.

Locality is not limiting.

Locality is not backward.

Locality is the scale at which human beings thrive.

And this is the doorway into the next part of the argument:

If locality is the natural scale of life, then we need a system that is built around locality – not around centralisation, abstraction, or money.

We need a system that:

- restores real life

- restores real value

- restores real contribution

- restores real community

- restores real governance

- restores real independence

- restores real health

This is where LEGS enters the picture.

LEGS is not an idea.

LEGS is not a theory.

LEGS is not an ideology.

LEGS is the practical structure that makes locality work – economically, socially, and politically.

And the first step in that structure is the Basic Living Standard.

SECTION 7 – The Basic Living Standard: Security for Real Life

If locality is the natural scale of human life, then the next questions are simple:

What stops people from living locally today?

What prevents people from reconnecting with real life?

What keeps them trapped in the abstract world?

The answer is fear.

Not dramatic fear.

Not panic.

Not terror.

A quieter fear – the fear of falling.

The fear of not being able to pay the rent.

The fear of not being able to heat the home.

The fear of not being able to feed the family.

The fear of losing work.

The fear of losing stability.

The fear of losing everything.

This fear is the glue that holds the abstract world together.

It is the mechanism that keeps people compliant, exhausted, distracted, and dependent.

It is the reason people stay in jobs that drain them.

It is the reason people accept systems that harm them.

It is the reason people tolerate centralisation, even when it destroys their communities.

It is the reason people cannot step back into real life, even when they can see the doorway.

Fear is the invisible chain that binds people to the abstract world.

And that is why the Basic Living Standard exists.

The Basic Living Standard removes the fear that keeps people trapped in the abstract

The Basic Living Standard (BLS) is not a benefit.

It is not welfare.

It is not charity.

It is not a safety net.

It is the foundation of a healthy society – the point at which survival is no longer tied to employment, and life is no longer held hostage by money.

The BLS guarantees that every person who works a full week at the lowest legal wage can meet all of their essential needs:

- food

- housing

- heat

- water

- clothing

- healthcare

- transport

- communication

- basic participation in community life

This is not generosity.

This is not ideology.

This is not utopian.

This is the minimum requirement for a real life.

Because without security, people cannot live locally.

Without security, people cannot contribute freely.

Without security, people cannot think clearly.

Without security, people cannot be healthy – physically or mentally.

Without security, people cannot resist centralisation.

Without security, people cannot step out of the abstract world.

The BLS removes the fear that centralisation depends on.

It breaks the coercive link between survival and employment.

It breaks the psychological link between money and worth.

It breaks the structural link between centralisation and control.

It gives people the ground beneath their feet.

The BLS makes locality possible again

Locality is not just a preference. It is a way of living that requires stability.

You cannot grow food if you are terrified of losing your home.

You cannot contribute to your community if you are working three jobs to survive.

You cannot learn real skills if you are constantly firefighting your finances.

You cannot participate in local governance if you are exhausted by insecurity.

You cannot build a real life if you are trapped in the abstract one.

The BLS creates the conditions in which locality can flourish.

It gives people the freedom to:

- choose meaningful work

- contribute to their community

- learn real skills

- participate in local governance

- grow food

- support neighbours

- build resilience

- live with dignity

The BLS is not the end of the journey. It is the beginning.

It is the point at which people can finally lift their heads from the grind of survival and see the world around them – the real world, not the abstract one.

The BLS restores the meaning of contribution

In the abstract world, work is a transaction.

In the real world, work is a contribution.

The BLS makes this shift possible.

When survival is guaranteed, people no longer work out of fear.

They work out of purpose.

They work out of interest.

They work out of ability.

They work out of connection.

They work out of contribution.

This is the foundation of a healthy local economy.

Not competition.

Not scarcity.

Not extraction.

Not centralisation.

Contribution.

And contribution only becomes possible when people are no longer trapped in the abstract world by fear.

The BLS is the first structural step back into real life

Locality is the natural scale of human life. But locality cannot function without security.

The BLS provides that security.

It is the point at which:

- fear dissolves

- agency returns

- contribution becomes possible

- community becomes real

- locality becomes viable

- centralisation loses its grip

- abstraction loses its power

The BLS is the foundation of LEGS because it is the foundation of real life.

It is the moment where the abstract world begins to fall away, and the real world begins to reappear.

And once the foundation is in place, the next step becomes clear:

Food must return to the centre of life.

Because food is the centre of locality.

And locality is the centre of everything real.

SECTION 8 – Beyond Food: Recognising Abstraction Everywhere

Food is the clearest example of how life has been lifted out of the real and placed into the abstract. But it is only the doorway. Once you step through it, you begin to see the same pattern everywhere.

Because the truth is this:

We are not just eating in the abstract.

We are living in the abstract.

Food simply makes the invisible visible.

When you realise that your relationship with food has become abstract, you begin to notice that your relationship with almost everything else has too.

Work has become abstract

Work used to be something people did for each other – a contribution to the life of the community. You could see the value of your work. You could see who it helped. You could see the difference it made.

Today, work is defined by:

- job titles

- performance metrics

- compliance systems

- productivity dashboards

- wages

- contracts

- HR policies

Work has become a transaction, not a contribution.

You don’t see who benefits.

You don’t see the outcome.

You don’t see the meaning.

You only see the abstraction.

And because work is abstract, it is unhealthy – mentally, emotionally, socially.

Value has become abstract

Value used to be rooted in usefulness, skill, care, and contribution.

Today, value is defined by price – a number that often has no relationship to the real worth of anything.

A handmade loaf of bread is “worth” less than a factory loaf.

A neighbour who cares for an elderly parent is “worth” nothing in economic terms.

A farmer who grows real food is “worth” less than a corporation that processes it.

Price has replaced meaning.

Money has replaced value.

Abstraction has replaced reality.

Governance has become abstract

Governance used to be local, human, and accountable.

Decisions were made by people who lived among those affected by them.

Today, governance is:

- distant

- bureaucratic

- centralised

- opaque

- unaccountable

Policies are written by people who will never meet the communities they shape.

Rules are imposed by people who will never experience their consequences.

Governance has become abstract – and therefore unhealthy.

Community has become abstract

Community used to be lived.

It used to be physical.

It used to be relational.

It used to be local.

Today, “community” is:

- a slogan

- a marketing term

- a digital group

- a brand identity

- a political talking point

People live near each other, but not with each other.

They share space, but not life.

They share information, but not responsibility.

Community has become abstract – and therefore fragile.

Identity has become abstract

Identity used to be shaped by:

- relationships

- contribution

- place

- experience

- responsibility

- community

Today, identity is shaped by:

- job titles

- income brackets

- digital profiles

- algorithms

- branding

- labels

Identity has become abstract – and therefore unstable.

Food is not the whole story – it is the proof

Food is the example that exposes the pattern.

Because food cannot be abstract without consequences.

Food cannot be centralised without harm.

Food cannot be disconnected from daily life without disconnecting people from life itself.

Food shows us the truth we have forgotten:

Local = real

Local = grounding

Local = healthy

Abstract = false

Abstract = distancing

Abstract = unhealthy

And once you see this in food, you begin to see it everywhere.

You begin to see that the abstract world is not natural.

You begin to see that the abstract world is not inevitable.

You begin to see that the abstract world is not healthy.

You begin to see that the abstract world is not sustainable.

You begin to see that the abstract world is not human.

And you begin to see why life feels the way it does.

Food is the doorway. But the destination is understanding the entire structure of the abstract world – and why we must leave it behind.

And that brings us to the next step:

If abstraction is the problem, and locality is the solution, then we need a system built entirely around locality.

That system is LEGS.

SECTION 9 – LEGS: Rebuilding Real Life

By now, the pattern is clear:

- The abstract world is unhealthy.

- Centralisation keeps life abstract.

- Locality is the natural scale of human life.

- The Basic Living Standard removes the fear that keeps people trapped in the abstract.

But recognising the problem is only half the journey.

The next step is understanding the structure that replaces it.

Because locality is not just a feeling.

It is not just a preference.

It is not just a philosophy.

Locality requires a system – a practical, grounded, human system – that allows people to live real lives again.

That system is the Local Economy & Governance System (LEGS).

LEGS is not an ideology.

LEGS is not a political programme.

LEGS is not a utopian dream.

LEGS is a design – a structure built around the natural scale of human life.

It is the opposite of the abstract world.

It is the opposite of centralisation.

It is the opposite of the money‑centric system.

LEGS is what life looks like when it returns to the local.

LEGS begins with a simple truth: people are the value of the economy

In the abstract world, value is defined by money.

In the real world, value is defined by people.

LEGS restores this truth.

It recognises that:

- people create value

- people sustain communities

- people maintain the environment

- people are the economy

Money is not the centre.

People are.

This single shift changes everything.

Because when people are the value, the economy must be built around people – not the other way around.

LEGS restores the natural relationship between people, work, and community

In the abstract world, work is a transaction.

In the real world, work is a contribution.

LEGS makes this shift possible by:

- removing fear through the Basic Living Standard

- grounding work in the needs of the community

- recognising contribution in all its forms

- ensuring that work is visible, meaningful, and connected to real life

Work becomes something you do with your community, not something you do for a distant system.

This is how work becomes healthy again – mentally, physically, socially.

LEGS restores locality to the centre of economic life

The abstract world depends on distance.

LEGS depends on proximity.

It brings:

- production

- exchange

- governance

- responsibility

- contribution

- decision‑making

back to the scale where life is actually lived.

This is not small.

This is not limiting.

This is not backward.

This is the scale at which human beings thrive.

LEGS makes food local again – because food is the anchor of real life

Food is not the whole story, but it is the centre of the story.

Because food is the one part of life that cannot be abstract without consequences.

LEGS restores:

- local food production

- local food processing

- local food exchange

- local food skills

- local food resilience

Food becomes part of daily life again – not a distant system controlled by people you will never meet.

And when food becomes local, life becomes local.

LEGS restores governance to the people who live with the consequences

In the abstract world, governance is distant and unaccountable.

In the real world, governance is local and human.

LEGS replaces:

- hierarchy with participation

- bureaucracy with responsibility

- distance with proximity

- abstraction with lived experience

Decisions are made by the people who live with the outcomes – not by distant institutions.

This is what real democracy looks like.

This is what real accountability looks like.

This is what real community looks like.

LEGS is not a theory – it is a practical system built on natural principles

LEGS works because it is built on the same principles that have sustained human life for thousands of years:

- locality

- contribution

- reciprocity

- transparency

- shared responsibility

- community

- stewardship

- human scale

These are not political ideas.

These are human truths.

LEGS simply gives them structure.

LEGS is the system that replaces the abstract world

The abstract world is collapsing – socially, economically, environmentally, psychologically.

LEGS is not a reaction to that collapse.

LEGS is the alternative that makes sense once you understand why the collapse is happening.

Because LEGS is:

- local where the abstract world is centralised

- real where the abstract world is false

- human where the abstract world is mechanical

- healthy where the abstract world is harmful

- grounded where the abstract world is unstable

- meaningful where the abstract world is empty

LEGS is not the future because it is new.

LEGS is the future because it is natural.

It is the structure that allows people to live real lives again – lives that are grounded, connected, meaningful, and healthy.

And once you see the abstract world clearly, LEGS stops looking radical.

It starts looking obvious.

SECTION 10 – The Revaluation: Seeing the Real World Anew

There is a moment – sometimes sudden, sometimes gradual – when the abstract world stops feeling normal.

A moment when the distance, the confusion, the instability, the disconnection, the exhaustion, the sense that life is happening somewhere else finally becomes visible.

A moment when you realise that the world you have been living in is not the real world at all – it is a constructed world, an abstract world, a world built on distance, centralisation, and money.

That moment is the beginning of The Revaluation.

The Revaluation is not a policy.

It is not a programme.

It is not a political movement.

The Revaluation is a shift in perception – a change in how you see value, meaning, contribution, community, and life itself.

It is the moment when you stop accepting the abstract world as inevitable, and begin to see it for what it is: a system built on distance, dependency, and fear.

And it is the moment when you begin to see locality – real life – again.

The Revaluation begins when you see the abstract world clearly

For most people, the abstract world is invisible because it is normal.

We grow up inside it.

We are educated inside it.

We work inside it.

We consume inside it.

We are governed inside it.

We mistake the abstract for the real because we have never known anything else.

But once you see the pattern – once you see how food has become abstract, how work has become abstract, how value has become abstract, how governance has become abstract – you cannot unsee it.

You begin to notice the distance everywhere.

You begin to notice the disconnection everywhere.

You begin to notice the centralisation everywhere.

You begin to notice the harm everywhere.

This is the first stage of The Revaluation: seeing clearly.

The Revaluation deepens when you understand what locality really means

Locality is not small.

Locality is not nostalgic.

Locality is not backward.

Locality is the natural scale of human life.

It is the scale at which:

- meaning is created

- relationships are formed

- contribution is visible

- responsibility is shared

- governance is human

- food is real

- work is purposeful

- value is grounded

- identity is stable

- health is supported

Locality is not a political idea.

Locality is a human truth.

And once you see locality clearly, you begin to understand what has been taken from you – and what can be restored.

This is the second stage of The Revaluation: understanding deeply.

The Revaluation becomes real when you recognise your own place in it

The abstract world teaches people to feel powerless.

It teaches people to believe that change is something done by others.

It teaches people to believe that systems are fixed, permanent, immovable.

But once you see the abstract world clearly, and once you understand locality deeply, something else happens:

You begin to feel your own agency again.

You begin to feel your own value again.

You begin to feel your own contribution again.

You begin to feel your own connection again.

You begin to feel your own responsibility again.

You begin to feel your own humanity again.

This is the third stage of The Revaluation: reclaiming yourself.

The Revaluation is the bridge between the abstract world and the real one

The Revaluation is not the end of the journey. It is the beginning.

It is the moment when:

- the abstract world becomes visible

- the real world becomes imaginable

- locality becomes desirable

- centralisation becomes unacceptable

- fear becomes unnecessary

- contribution becomes meaningful

- community becomes possible

- LEGS becomes obvious

The Revaluation is the shift in consciousness that makes the return to real life possible.

It is the moment when the reader – without being told – begins to feel:

“I want to live in the real world again.”

And that is the doorway into the final section.

Because once you see the abstract world clearly, and once you understand locality deeply, and once you recognise your own agency, the next questions become simple:

What does a real life actually look like?

And how do we build it?

That is where we go next.

SECTION 11 – What Local Life Truly Means

By now, the shape of the truth is visible.

You can see the abstract world for what it is: a system built on distance, centralisation, and money – a system that disconnects people from the real, from each other, and from themselves.

You can see how food exposes the pattern – not because food is the whole story, but because food refuses to be abstract without consequences.

You can see how centralisation maintains the abstract world by removing life from the local and placing it in the hands of people who never experience the outcomes of their decisions.

You can see how locality is the natural scale of human life – the scale at which meaning, health, contribution, and community become possible again.

You can see how the Basic Living Standard removes the fear that keeps people trapped in the abstract world.

You can see how LEGS provides the structure that allows real life to function again – economically, socially, and politically.

And you can see how The Revaluation is not a policy or a programme, but a shift in consciousness – the moment when the real world becomes visible again.

So what does a real, local, human life actually look like?

It looks like this:

A life where food is part of daily experience, not a distant system

You know where your food comes from.

You know who grew it.

You know how it was made.

You know what it means.

Food becomes grounding again – physically, mentally, emotionally, socially.

Food becomes a relationship, not a product.

Food becomes the anchor of real life.

A life where work is contribution, not coercion

You work because you want to contribute, not because you fear falling.

You see the impact of what you do.

You see who benefits.

You see the meaning.

Work becomes human again.

Work becomes visible again.

Work becomes part of community life again.

A life where value is real, not abstract

Value is no longer defined by price.

Value is defined by usefulness, contribution, care, skill, and meaning.

A neighbour who helps an elder is valued.

A farmer who grows real food is valued.

A craftsperson who repairs what others throw away is valued.

A parent who raises children is valued.

Value becomes grounded again.

A life where governance is local, human, and accountable

Decisions are made by people who live with the consequences.

Governance is not distant.

Governance is not abstract.

Governance is not bureaucratic.

It is participatory.

It is transparent.

It is relational.

It is human.

This is what real democracy looks like.

A life where community is lived, not imagined

Community is not a slogan.

It is not a digital group.

It is not a marketing term.

Community is the people you see, speak to, help, support, and rely on.

It is the people who share responsibility with you.

It is the people who share the place with you.

It is the people who share life with you.

Community becomes real again.

A life where identity is grounded, not constructed

Identity is no longer defined by job titles, income brackets, or digital profiles.

Identity is shaped by:

- contribution

- relationships

- place

- responsibility

- experience

- community

Identity becomes stable again.

A life where health is supported by the structure of daily living

Locality reduces stress.

Contribution reduces anxiety.

Community reduces loneliness.

Real food improves physical health.

Real relationships improve mental health.

Real responsibility improves emotional health.

Health becomes a natural outcome of real life – not a service purchased in the abstract world.

A life where the environment is cared for because people live close to it

When life is local, the environment is not an idea.

It is the place you live.

It is the soil you depend on.

It is the water you drink.

It is the air you breathe.

Stewardship becomes natural again.

A life where money is a tool, not a master

Money circulates.

Money supports.

Money facilitates.

Money does not dominate.

Money does not accumulate.

Money does not control.

Money becomes what it always should have been: a tool for exchange, nothing more.

A life where fear no longer dictates behaviour

The Basic Living Standard removes the fear of falling.

And when fear disappears, something else appears:

- agency

- dignity

- contribution

- creativity

- responsibility

- connection

- meaning

Fear is the foundation of the abstract world.

Security is the foundation of the real one.

A life where the abstract world finally loses its power

Once you see the abstract world clearly, it stops feeling inevitable.

Once you understand locality deeply, it stops feeling small.

Once you recognise your own agency, you stop feeling powerless.

Once you see LEGS, you stop feeling trapped.

And once you experience even a glimpse of real life – grounded, local, human – the abstract world begins to feel as strange as it truly is.

This is a doorway

This essay is not the whole journey.

It is a doorway.

It is the moment where the abstract world becomes visible, and the real world becomes imaginable.

It is the moment where you begin to see that the life you have been living is not the only life available.

It is the moment where you begin to understand that locality is not a step backward – it is the only step forward that makes sense.

It is the moment where LEGS stops looking radical and starts looking obvious.

It is the moment where The Revaluation begins.

And once you step through this doorway, the rest of the work – the deeper structures, the practical mechanisms, the full system – are waiting for you.

Not as theory.

Not as ideology.

Not as abstraction.

But as the architecture of a real, local, human life.

Closing Reflection

When the Real World Stops Looking Abstract

If you have reached this point, something important has already happened.

You have seen the abstract world clearly enough to recognise its shape.

You have seen how distance, centralisation, and money have replaced the real with the artificial.

You have seen how food reveals the pattern.

You have seen how locality restores what abstraction removes.

You have seen how the Basic Living Standard and LEGS make real life possible again.

But more importantly, you have felt something shift.

The real world – the local, the human, the grounded – no longer looks abstract.

It no longer looks naïve.

It no longer looks unrealistic.

It looks obvious.

This is the beginning of The Revaluation – the moment when the real becomes visible again, and the abstract begins to lose its power.

It is the moment when you realise that rejecting the real was never a rational choice – it was a conditioned response.

It is the moment when you recognise that the systems we inherited were never designed for human wellbeing.

It is the moment when you understand that stepping back into the real is not a risk – it is a return.

A return to meaning.

A return to agency.

A return to contribution.

A return to community.

A return to health.

A return to life.

This essay is not the end of the journey.

It is the threshold.

Beyond this point lies the deeper work – the full architecture of The Local Economy & Governance System, the Basic Living Standard, the Local Market Exchange, the redefinition of work, the restoration of value, the rebuilding of governance, and the practical steps that make a real, local, human life possible again.

If the abstract world once felt like the only world available, and the real world once felt like an abstraction, that illusion has now begun to dissolve.

You are standing at the doorway.

The rest of the journey is yours to choose.

Further Reading: Stepping Beyond Abstraction

The essay “Out of the Abstract” invites readers to step through a doorway – leaving behind a world shaped by distance, centralisation, and abstraction, and returning to a life grounded in locality, contribution, and real value.

The following readings are curated to guide you further along this path, each expanding on the foundational concepts and practical steps introduced in the essay.

Whether you seek philosophical context, practical frameworks, or blueprints for change, these resources offer a coherent continuation of the journey.

1. Foundations of a People-First Society

The Philosophy of a People-First Society

https://adamtugwell.blog/2026/01/02/the-philosophy-of-a-people-first-society/

Summary:

This piece lays the philosophical groundwork for a society that prioritises human wellbeing over abstract systems. It explores the values, principles, and mindset shifts necessary to move from centralised, money-centric structures to local, people-first communities. The essay provides context for why locality is not just preferable, but essential for meaningful, healthy lives.

2. The Architecture of Locality: LEGS and Its Ecosystem

The Local Economy & Governance System (LEGS) – Online Text

https://adamtugwell.blog/2025/11/21/the-local-economy-governance-system-online-text/

Summary:

This comprehensive resource details the LEGS framework, the practical system designed to restore locality as the natural scale of human life. It explains how LEGS re-centres value, work, and governance around people and communities, providing the structure for economic and social resilience.

Visit the LEGS Ecosystem

https://adamtugwell.blog/2025/12/31/visit-the-legs-ecosystem/

Summary:

This link offers a guided exploration of the LEGS ecosystem, showcasing real-world applications, solutions, and the impact of locality-driven systems. It’s an invitation to see how theory can become practice, and how communities can thrive when grounded in local principles.

From Principle to Practice: Bringing the Local Economy & Governance System to Life – Full Text

https://adamtugwell.blog/2025/12/27/from-principle-to-practice-bringing-the-local-economy-governance-system-to-life-full-text/

Summary:

This essay bridges the gap between conceptual understanding and practical implementation of LEGS. It provides actionable steps, case studies, and reflections on how communities can reclaim agency and rebuild local systems.

3. Revaluing Work, Contribution, and Community

The Contribution Culture: Transforming Work, Business, and Governance for Our Local Future with LEGS

https://adamtugwell.blog/2025/12/30/the-contribution-culture-transforming-work-business-and-governance-for-our-local-future-with-legs/

Summary:

This essay explores the shift from transactional work to meaningful contribution, showing how LEGS enables a culture where work is valued for its impact on community and wellbeing. It discusses the transformation of business and governance when contribution, not extraction, becomes the central principle.

4. Food, Security, and Community Resilience

Foods We Can Trust – A Blueprint for Food Security and Community Resilience in the UK

https://adamtugwell.blog/2025/12/15/foods-we-can-trust-a-blueprint-for-food-security-and-community-resilience-in-the-uk-online-text/

Summary:

Building on the essay’s theme that food is the anchor of real life, this blueprint offers practical strategies for restoring local food systems, ensuring food security, and strengthening community resilience. It demonstrates how food education, production, and sharing can reconnect people to the real world.

5. The Basic Living Standard: Security as Foundation

The Basic Living Standard Explained

https://adamtugwell.blog/2025/10/24/the-basic-living-standard-explained/

Summary:

This resource clarifies the concept of the Basic Living Standard (BLS), the foundation that removes fear and enables people to live locally. It explains how BLS guarantees essential needs, liberates individuals from the coercion of abstract systems, and creates the conditions for genuine contribution and community.

6. Centralisation and Its Consequences

Centralisation Only Rewards Those at the Centre

https://adamtugwell.blog/2026/01/31/centralisation-only-rewards-those-at-the-centre/

Summary:

This essay exposes the mechanisms and consequences of centralisation, showing how it perpetuates abstraction, distance, and inequality. It complements the main text’s argument by detailing why centralisation undermines locality and how reclaiming the local is essential for health, agency, and democracy.

Conclusion

Together, these readings form a coherent pathway for anyone seeking to move “out of the abstract” and into a reality that is local, human, and whole.

They offer philosophical depth, practical frameworks, and actionable blueprints – each one a step further into the architecture of a life that makes sense.

Frequently Asked Questions & Common Objections

1. Isn’t locality just nostalgia or romanticism?

Answer:

Locality is not about longing for the past or rejecting progress. It’s the natural scale at which human beings thrive – where relationships, meaning, and health are experienced directly.

The argument for locality is grounded in practical realities: when life is lived locally, people are more resilient, communities are stronger, and systems are more accountable. Locality is not backward; it’s the foundation for a future that makes sense.

2. Is centralisation always bad?

Answer:

Centralisation isn’t inherently evil, but when it becomes the dominant organising principle, it creates distance, removes empathy, and undermines accountability.

The problem arises when centralisation replaces local agency and turns lived experience into abstraction.

The goal is not to eliminate all central systems, but to restore balance – ensuring that decisions and value creation happen at the scale where people actually live.

3. Isn’t locality inefficient compared to global systems?

Answer:

Efficiency is often measured in terms of speed, scale, or profit, but these metrics can hide the true costs: loss of meaning, health, and resilience.

Local systems may appear less “efficient” in narrow economic terms, but they excel at creating stability, agency, and wellbeing.

Locality is not small or limiting – it’s the scale at which human beings can flourish, adapt, and sustain themselves.

4. How can locality work in urban or highly connected environments?

Answer:

Locality is not limited to rural areas. Urban communities can – and do – build local food systems, governance structures, and networks of mutual support.

The principles of locality apply wherever people live: grounding life in relationships, contribution, and shared responsibility.

Technology can be harnessed to strengthen local connections, not just to centralise control.

5. What about global challenges like climate change or pandemics?

Answer:

Global challenges require cooperation across scales, but local resilience is essential for effective response.

Local systems are better able to adapt, mobilise, and care for their members.

The argument is not for isolation, but for restoring the capacity of communities to act meaningfully – while still collaborating globally where needed.

6. Isn’t the Basic Living Standard (BLS) just another form of welfare?

Answer:

The BLS is not welfare, charity, or a safety net.

It’s a structural guarantee that every person who works a full week at the lowest legal wage can meet their essential needs.

The BLS removes the fear that keeps people trapped in the abstract world, enabling genuine contribution, agency, and community. It’s the foundation for a healthy society, not a handout.

7. How does LEGS differ from other economic or governance models?

Answer:

LEGS – The Local Economy & Governance System – is not an ideology or utopian dream. It’s a practical structure built around the natural scale of human life.

LEGS centres value, work, and governance on people and communities, rather than money or distant institutions.

It restores visibility, accountability, and meaning to everyday life.

8. Isn’t this vision unrealistic in today’s world?

Answer:

What’s truly unrealistic is expecting people to thrive in systems that disconnect them from meaning, agency, and community.

The abstract world is collapsing – socially, economically, and environmentally.

The vision of locality, BLS, and LEGS is not radical; it’s obvious once you see the costs of abstraction.

The journey begins with a shift in consciousness, and practical steps are possible for individuals, communities, and policymakers.

9. How do I start making my life more local and real?

Answer:

Begin by noticing where abstraction has replaced reality in your daily life – food, work, relationships, governance.

Seek out opportunities to reconnect: grow or source local food, participate in community initiatives, support local businesses, and engage in local decision-making.

The journey is incremental, but every step toward locality restores meaning, agency, and health.

Glossary of Key Terms

Abstraction

The process by which real, lived experiences are replaced by distant systems, representations, or mechanisms.

In the context of this book, abstraction refers to the way modern life is organised around concepts, structures, and processes that are removed from direct human experience.

Locality

The natural scale of human life, where relationships, value, and meaning are experienced directly.

Locality emphasises living, working, and governing at the community or human scale, as opposed to distant or centralised systems.

Centralisation

The concentration of power, decision-making, and resources in distant institutions or authorities, often at the expense of local agency and accountability.

Centralisation is identified as the engine that perpetuates abstraction and undermines local resilience.

Basic Living Standard (BLS)

A structural guarantee that every person who works a full week at the lowest legal wage can meet all essential needs – food, housing, heat, water, clothing, healthcare, transport, communication, and basic participation in community life.

The BLS is designed to remove the fear that keeps people trapped in abstract systems.

Local Economy & Governance System (LEGS)

A practical framework for organising economic and social life at the local scale.

LEGS centres value, work, and governance on people and communities, restoring visibility, accountability, and meaning to everyday life.

Contribution

Work or effort that benefits the community or others, as opposed to transactional labour driven by fear or necessity.

Contribution is valued for its impact on wellbeing and community, not just its economic output.

Revaluation

A shift in consciousness where individuals begin to see the abstract world clearly, understand the importance of locality, and reclaim agency, meaning, and connection.

The Revaluation marks the beginning of the journey back to real, local, human life.

Food Security

The condition in which communities have reliable access to sufficient, safe, and nutritious food produced and distributed locally.

Food security is presented as a cornerstone of local resilience and wellbeing.

Community

A group of people who share responsibility, relationships, and lived experience at the local scale.

Community is distinguished from abstract or digital groups by its grounding in place and mutual support.

Agency

The capacity of individuals or communities to act meaningfully, make decisions, and shape their own lives.

Agency is diminished by abstraction and centralisation, but restored through locality and the Basic Living Standard.

Resilience

The ability of individuals or communities to adapt, recover, and thrive in the face of challenges.

Local systems are described as more resilient than centralised ones because they are grounded in relationships and direct experience.